Polite Obscenities

Polite Obscenities: Graphic Designer as Reluctant Citizen

presentation to the ICOGRADA Sydney 99 International Design Congress

Watching television a while back, just after Dr Spock died, I caught an interview with the co-author of the most recent edition of Spock’s famous book on child rearing. The interviewer asked what the difference was between Spock’s ideas regarding pediatric psychology and his political beliefs (being infamous also for his anti-Vietnam war stance). The co-author responded by saying that there was no difference. They were the same thing. He said Spock believed you could raise a child in a supportive and loving manner, but if the child’s community is corrupted by racism and conflict, and their environment is degraded, then in spite of a parents best efforts and intentions, on some level the child will be damaged.

So, in a way, this is how I feel about my work: that it is false to try and separate what I create from a broader social context.

Designers often have little to say. We’ve learned to hold our tongues. But this silence is a polite obscenity. Our ideas can, and sometimes should offend – should sometimes shake what our audience feels and believes. Our role as designer is not divorced from our role as citizen.

The word idea derives from the Greek verb to see. The very way we think is embedded in western culture as a visual paradigm. Looking, seeing and knowing are intertwined. What we see is not simply an objective optical impression, a natural physical ability. Seeing is related to the ways our society has arranged its forms of knowledge, its strategies of power and its systems of desire.1 The relationship between vision and truth is mostly social, not formal.2

Design is a language of images, of signs that give meaning to the world. As designers, we don’t just reflect the world in our work, we help create it. This meaning is constructed within our language, not just represented by it.

This language of images we manipulate actually consists of competing ways of giving meaning to the world. When one way wins, another must loose. A position of power is established. Straight or gay, black or white, rich or poor, man or woman. Our visual language becomes a site for the organisation of social power. So the struggle to meet a client’s brief becomes also a political struggle. How did that happen! Why is it so hard for designers to accept the social consequences of their work? We dodge any notions of a subjective reality with gymnastic agility.

Australian art critic Giles Auty quotes Cicero: “Only a madman would maintain that the difference between virtue and vice is a matter of opinion and not of nature.” And goes on to say “Instead of worrying about opinions, perhaps the real business of significant art criticism is that of learning to see the fundamental nature of virtues and vices in art for what they are.”3

Many of us want to believe in this objective reality, this world of inherent embedded value and meaning beyond our control. Like we want to believe the mass killer is insane, or maybe even possessed by a devil. We want our own responsibility abdicated.

But as Bob Dylan sings: “All he believes are his eyes / And his eyes they just tell him lies” 4

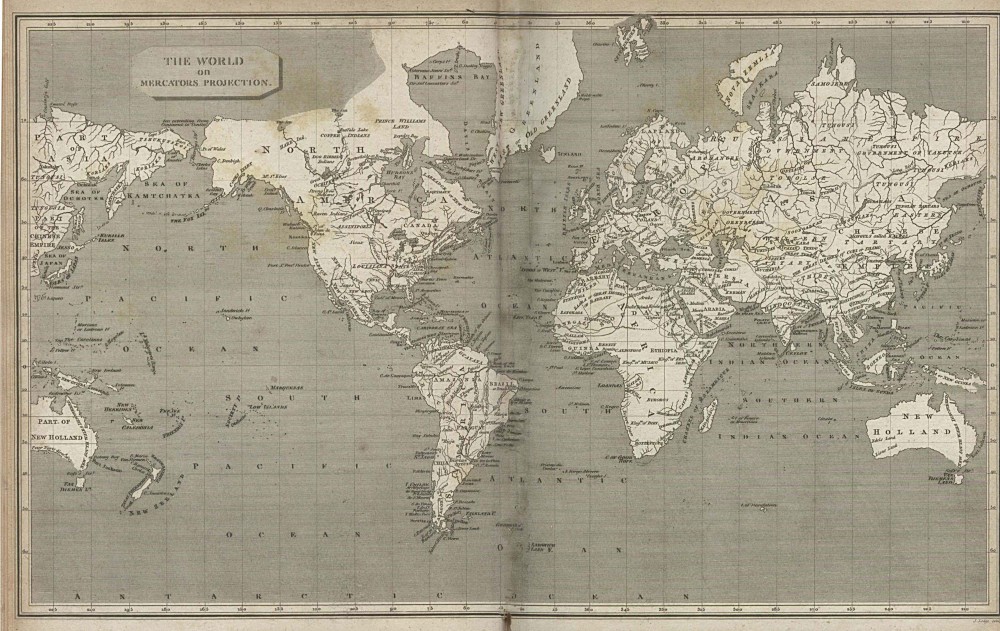

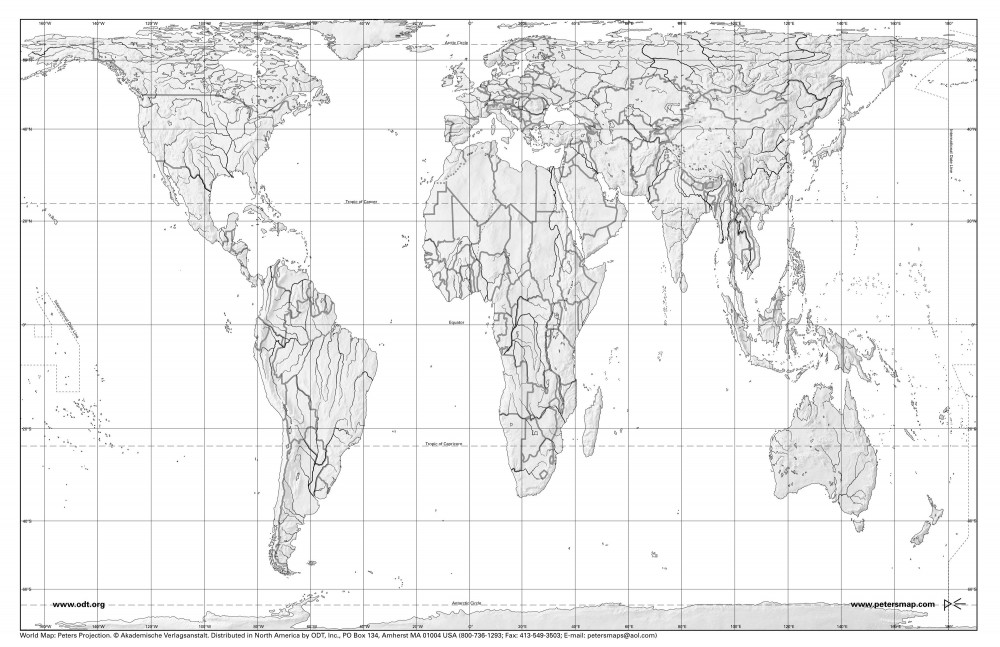

Consider the map from which every Australian school student begins to learn the geography of the world.

Notice the difference between the size of continents such as Africa and North America (they appear to be about the same size), or Scandinavia and India (they also look to be about the same size). Then compare the freely available yet rarely encountered Peters Projection Map.

Here, the actual relative size and scale of continents is shown, while the ubiquitous first map distorts the scale and reduces the size of mainly black populated continents. (Africa which is approximately 30 mill sq km appears the same size as North America which is actually only 19 mill sq km, and India looks about the same size as Scandinavia even though it is about 3 times bigger.) So the values and concerns that informed the rendering of the first maps of the world continue to teach white Australian children about the superiority of their race and of a long dead empire. As the scale of the land-forms are distorted so are our own ideas of our selves and our place in the world.

We hear designers proclaim that they don’t ‘care about or respect’ politics. Fair enough, but we don’t need to care about or respect politics to acknowledge that the political processes we are inextricably part of, directly or indirectly shape our reality. There is no such thing as an apolitical stance. Not even for a designer. To ignore this is a VERY political stance.

The better designers we are, the more powerful our clients become. Our skills and talents have a tangible impact on our client’s presence in the community – on the reach and strength of their corporate grasp. And consequently, on the relative position of their competitors, and of their market obstacles (which are too often related to human rights, environmental issues, and other kinds of annoying inconveniences).

For designers this is now a comfortable contradiction. We argue our work can boost sales, move units and grow profits but we are also convinced, as David Carson put it, that ’graphic design will save the world right after rock and roll does.’5 So in a dizzy, self-induced state of schizophrenia we imagine we can’t change (let alone save) the world, yet we can conceivably help fuck it up.

Since the 1800’s political democracy and popular education has eroded the old ruling class monopoly on culture. The market place has become bloated with cultural products to satisfy the awakened public. New technologies reach us rapidly and cheaply – printing, recorded music, movies and the internet all entertain, educate and engage us. Our role as visual communicators in this communication revolution is not insignificant – our impact is real. If it is not, what exactly do clients pay for?

Design is often justified as enhancing competition, and therefore benefiting the public. As consumers we are secure and comfortable, even empowered, by our ability to choose between presented products and services. We can choose between Coke and Pepsi, McDonalds and KFC, or Shell or Mobil. The choices are endless; such is the dynamic nature of capitalism.

We trade in terms such as product differentiation, brand recognition, etc, etc. We offer ourselves to businesses to help argue their products case in the marketplace. Discerning consumers rely on us.

The problem with this rhetoric is that in the end, these choices are fundamentally trivial. At least in relation to the real choices and decisions that effect a person’s life. So is political apathy a product of the illusion of choice of consumption? John Berger wrote “Publicity turns consumption into a substitute for democracy.”6 Is our energy deflected away from real political choice to a decision over what car we drive or what beer we drink? If we don’t accept a social responsibility for the work we produce, then we may merely be “masking and compensating for all that which is undemocratic in our society.”7

This is a landscape where the shed skins of meaning litter our polluted vision of reality. Where value is constantly leeched from a fertile culture but gives nothing back. We bravely rip off style and we homogenise aesthetic diversity. We fuck promiscuously with typography and legibility but rarely with the dominant ideology. Here the radical becomes the mundane as the conformist plays the revolutionary. Is a new visual language really radical as an instrument of ruling political power? Or is this just form following the function of oppression? Are graphic designers worthy of a new creative status: author; information architect; or the coveted mantle artist, if our work is in the service of an ideology that at best divides and distracts us, and at worst starves and murders us.

An artist communicates a personal vision to other individuals. Often designers merely manufacture visual commodities for the marketplace. If we can begin to satisfy the cultural needs of society rather than exploiting them for profit and the power of a ruling class, then we can call ourselves whatever we want.

If we extend the cultural participation of our audience beyond the choice of buying or not buying, we extend our own role and value as cultural producers.

Design should do more than give people the illusion of choice, more than persuade or educate consumers. It should educate and inspire citizens. We should start by questioning the culture of publicity, it’s language. This is the manufacture of anxiety, of fear or desire. Often commercial design functions to produce feelings of dissatisfaction with the viewer and their place in society – though never, ever with society itself. The design also promises transformation, of an end to the dissatisfaction that has been manufactured.8 The actual product or service is usually incidental.

We need to question the processes by which, as Berger says, we “steal the self-love of the audience and offer it back to themselves for a price.”9 We need to stop being the puppets and pawns for irresponsible corporations who don’t even care about our work, except that it convinces their market of their lies.

These are the lies that generate then manipulate desire. Control over our desire is crippled and guided towards consumption as a kind of post-orgasmic cigarette. There is an absence that it promises to fulfil. But our desire is aimed at products so that in the end people and products are interchangeable. We identify with what we consume, not with what we produce. In this way design can obscure real contradictions in society by veiling important distinctions between people with the false categories of a persuasive visual culture. The true aspirations of a community, such as better education, health or transport are highjacked and end up as R2-D2 body wash and leather-trimmed 4WD’s. One problem designers face is that in reality any communication, any conveyed information is persuasive. All information modifies behaviour to different degrees. We can never communicate nothing. No signifier is without it’s signified.

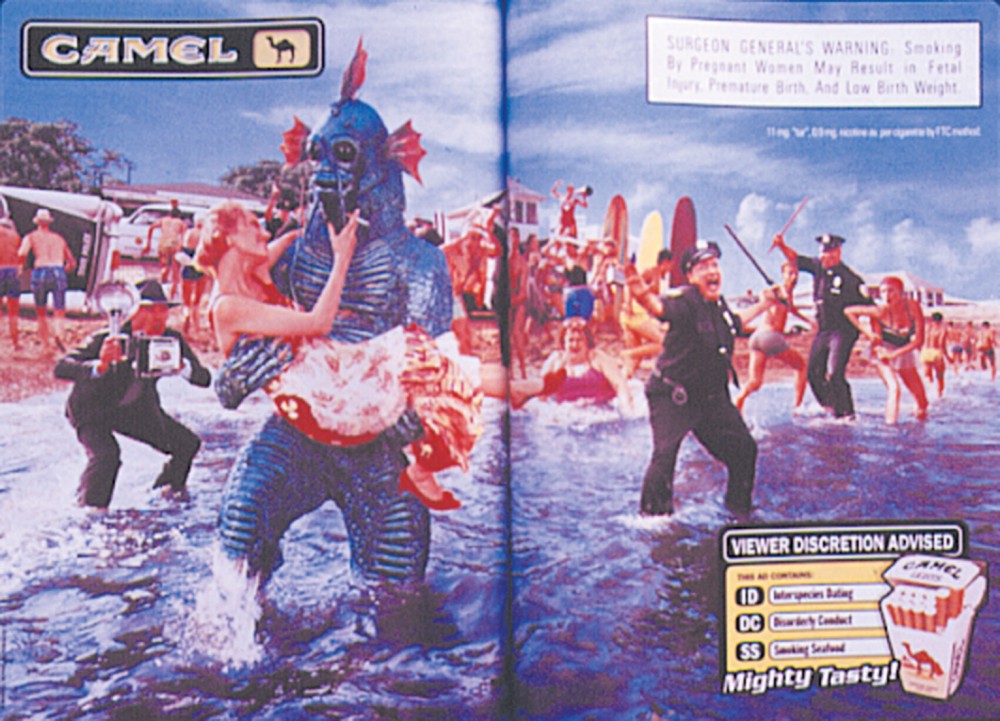

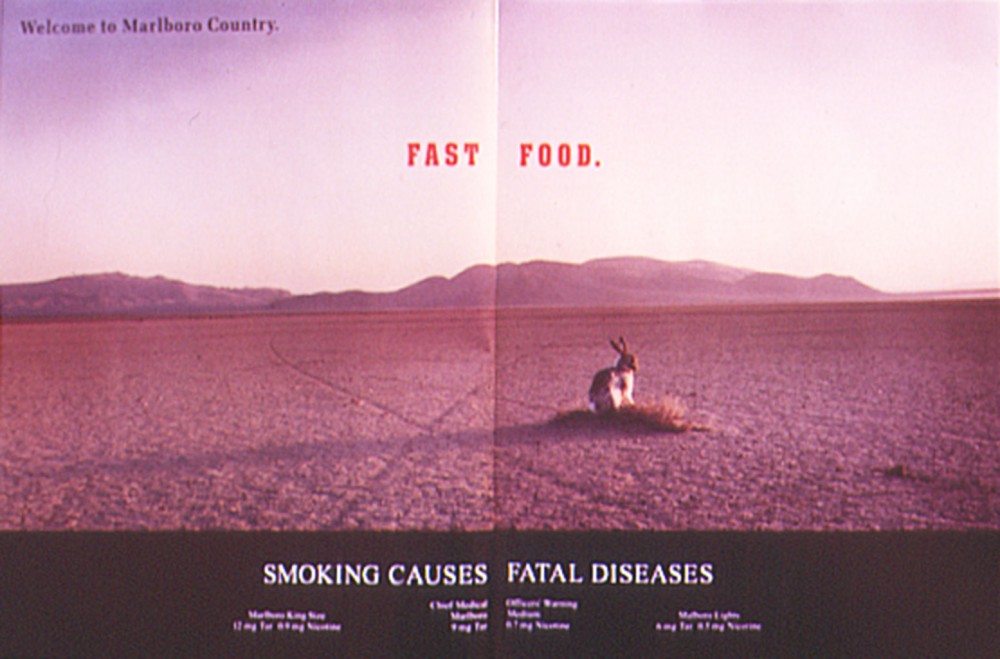

It’s not easy to claim these ads – or ads of this type – create or inflate desire. Surreal and ambiguous, the product is barely mentioned (except through the text of the Government health warning). However various polls and reports have found a link between smokers and advertising. For example, the 1990 Mori poll found nearly half of all smokers aged eleven to fourteen smoked Benson and Hedges. But over fifteens, having been exposed to the pre-surreal ads thought the brand to “safe or sensible”10 and smoked other brands.

Design is language, it is speech, it is discourse. But who is speaking this language of images? What is their position of power? What is their context? These sorts of questions should figure in a designer’s brief more than the conspiratorial marketing manipulations of demographic strategy. What is revealed and what is concealed? What is included and what is ignored? It’s also between the lines – in these absences – that our language lies naked. A picture’s worth a thousand words, and a thousand more for what it omits. We are responsible for the images we render, as well as those we render invisible. Comedian Lenny Bruce used to say, “the power of the word is in it’s suppression”11, and Foucault wrote “silence and secrecy are a shelter for power”12.

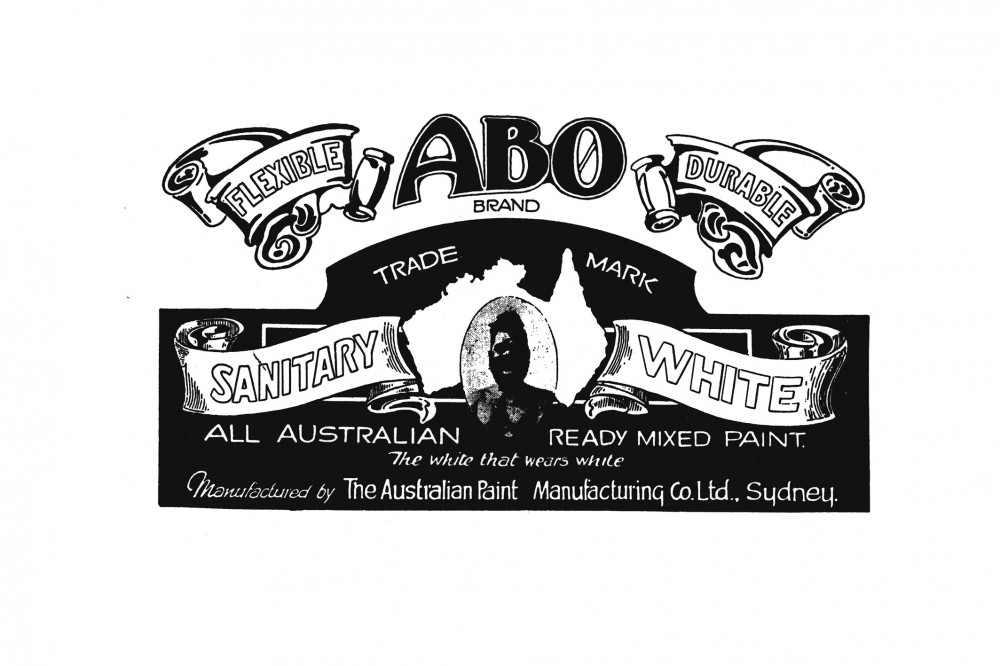

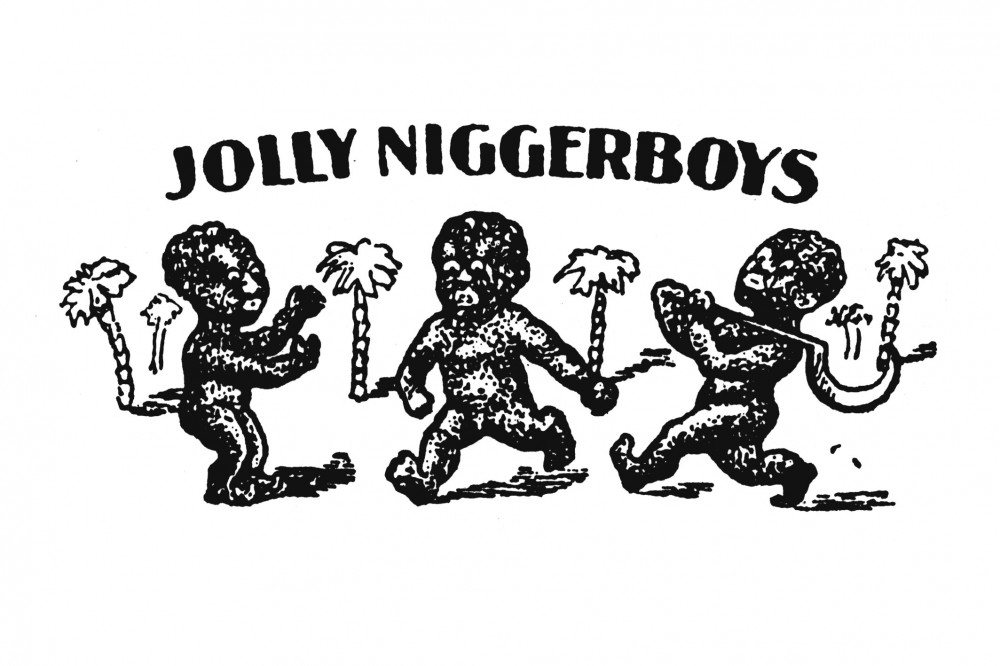

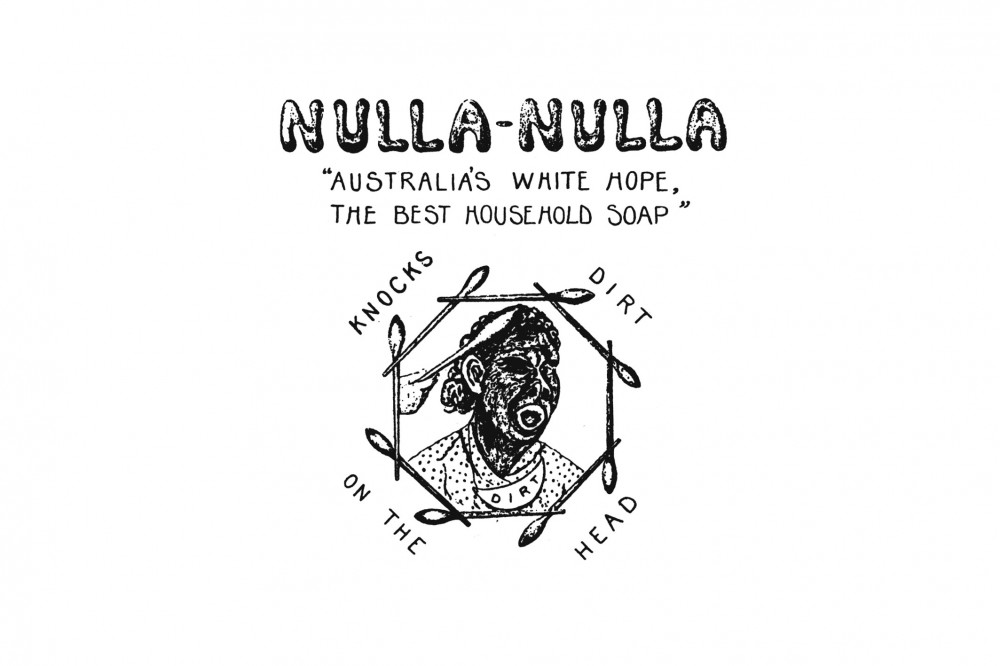

While the early Australian trade marks above reveal and construct certain national values of the time by what they show, many other texts communicate equally unambiguously through what is hidden. When looking at an old Expo 88 promotional program, I saw hundreds of images of the Host City, Brisbane, and of Australia, but only one image amongst them relating to Indigenous Australia (this a promotional book for the world’s biggest tourism exposition, a chance for Australians to advertise what we think is unique about our country and culture) Two hundred years ago in this place none of these structures displayed so proudly, or the values and concerns that built them even existed. So in a modern incarnation of the 1788 Terra Nullus lie, we erased Aboriginal Australia from our landscape and from our cultural consciousness.

Mostly, we don’t seem very interested in the social context and consequences of our work. Why not? The client, as producer or supplier is. They must consider the effects of their product or service on the community and environment. That’s not to say the cigarette manufacturer is necessarily acting responsibly, but in spite of their denials, they probably understand their product’s consequences. And the consumer often is – the proliferation of environment-friendly labelling is testament to this.

So why aren’t we? Do we feel as if we don’t have the right to question the client over practices we may find personally objectionable? It’s true that most of us are just happy to have work – the nature of it can be irrelevant. We don’t necessarily need to turn away every client that doesn’t use oxygen bleached, post consumer waste in their packaging. But we at least need to admit there ARE social and personal consequences to our creations, just as the client does, and just as our audience does.

If we ignore these dimensions of our role, we become complicit in a kind of erosion of our personal and collective identities as they are rebuilt from the discarded, empty surfaces of the products of consumption. We identify with what we consume and are alienated from what we produce. Is a personalised numberplate on a car, or a cartoon tie a radical expression of individuality or just a new way of conforming? Maybe being different is more than wearing a joke tie with an expensive suit, or overlapping layered typography in an expensive annual report? If not, then we’re just like the rebellious joke sock under the tailored trouser leg of society. Our degree of individualism and nonconformity is only ever as much as the corporate dress code permits.

We Australians have become a Lonely Crowd. We’re barely related to each other now as individuals or as part of a community. We are alienated together. Our common interests, values, traditions and concerns are exploited and abstracted for consumption. Designers objectify our audience. We even call them target markets. We aim and we fire, and if we’re good we pierce the bull’s eye. But like the cartoon violence of primetime television there is little blood and no grieving lover or family, no real consequences. While we’re busy blowing smoke from the empty barrel the victim is vomiting blood and dying in pain. When we approach individuals as consumers, and groups of people as markets, we are stalking them with intent – as hunters and killers. When we reduce an audience to a market we degrade their humanity. This is an act of violence – there is no room for empathy or exchange, only taking. When we’re looking down the barrel at our target market there is no room in our sights for the beauty of real life – the unmarketable change, pain, joy, subversion, failure, originality - the rich, unsettling, deep realities of being human.

As professional visual communicators, surely we should accept that the true value of our work is determined inevitably by its cultural, physical, spiritual and intellectual impact on the community. Not to mention its transmutative, alchemical, poetic and sometimes wildly liberating effect on us.

Capitalism survives by defining the public’s interests as narrowly as possible. Where this was once achieved by deprivation and repression, now it is achieved with the aid of visual communicators manufacturing the illusion of choice, and the distraction of real political empowerment.

But we can build our studios as laboratories of ideas for the frontiers of life, rather than factories of tricks for the showrooms of commerce. We can explore rather than ignore the relationship between the sensual, and the cultural & historical realms of design. Our role as visual problem solvers is inadequate – let’s now discover new questions as well as answers.

+

Jason Grant 1999

1&2 Chris Jenks Visual Culture 1995. 3 Giles Auty The Weekend Australian June 5-6 1999. 4 Bob Dylan License to Kill 1983. 5 David Carson The End of Print 1995. 6,7,8,&9 John Berger Ways of Seeing 1972. 10 MORI Poll 1990. 11 Lenny Bruce The Essential Lenny Bruce 1973. 12 Michel Foucault The History of Sexuality, Vol1 1981. 13 logos sourced from Mimo Cozzillino’s Symbols of Australia 1985.