Against Branding

Against Branding.

Design, Happiness & Conflict

An edited version of this essay was published in two parts on Design Observer.

The corporate scheming we call branding is boundless. What began as an outpost seems now to encompass and define the whole world, interpreting and explaining everything in its own terms. John Berger wrote: “The world smiles at us. It offers itself to us. And because everywhere is imagined as offering itself to us, everywhere is more or less the same.” Against such accusations of homogeneity branding is often defended by claiming heterogenous consumer choices as a form of empowerment, as if these myriad systematic distinctions added up to real diversity, as if these shopping prospects were anything more than trivial.

A more ambitious argument is that branding transcends corporate and commercial domains. Branding cheerleader Waly Olins claimed: “The influence, strategies and tactics of branding go way beyond this. Branding is playing a large and increasing part in politics, the nation, sport, culture, and the voluntary sector.” This defense is, however, its most significant indictment. Witness Trump brand vodka, steaks, casinos, and now presidencies. Even more than corporate legitimization and co-option, branding’s reconstitution of non-corporate entities as market-tamed subordinates is causing real harm. Branding has become an ideological Trojan horse, invading social and cultural realms traditionally resistant to corporate influence. It is promoted and accepted as a neutral tool when actually there is little it doesn’t frame and distort.

Donald Trump launching Trump Vodka in 2007. Associated Press

Donald Trump launching Trump Vodka in 2007. Associated Press

I want to examine this phenomenon in relation to design from the perspective of two concepts, happiness and conflict. Part One wades briefly into the big theme of happiness and what design means to branding in this realm. Part Two tackles design’s relationship to conflict, it’s culpability and possibilities.

Part 1: Happiness

Build your opponent a golden bridge to retreat across.

Sun Tzu

Designers know how to make you happy. We are proprietors of pleasure, merchants of merriment. We provide infinite affirmation. The world is more beautiful, comfortable, and prosperous, thanks to designers.

In commercial design, anxiety, fear, and self-doubt are often summoned towards the distant promise of happiness. Any happiness then lasts only long enough to deepen the feelings of insecurity aroused to motivate consumption. And the whole spectacle, the vast, irreconcilable distance between desire and satisfaction, is micromanaged by designers.

But it is a particular kind of happiness. It is as fickle and fleeting as instant gratification, and as shallow as stale comfort. Authentic contentment is as elusive as proverbial quicksilver. Of course, real happiness doesn’t necessarily endure either, as William Burroughs wrote in his notes as he was dying: “People blather about ‘happiness,’ like some permanent medium you can accrete around yourself and never want for anything again. The archetypal swindler’s line.” Making America “great again” is making pissed-off (white) Americans happy again.

Donald Trump signing a hat. Photograph by Matthew Cavanaugh/Getty Images

Donald Trump signing a hat. Photograph by Matthew Cavanaugh/Getty Images

And this is only half the story. The real story is invisible—it’s unseen because we are rewarded to look the other way: All this happiness is big trouble. The happiness created by corporate design doesn’t relieve the paralyzing tragedy and misery of the world; it just ignores or denies it. And this surface experience of the deep pain of others is itself an enabling condition of ideological affliction.

Economists have helped bring us to the brink. Unflinchingly, they watch as markets crumble, crash, and surge. Now they are also measuring happiness, and have actually calculated it would take roughly $60,000 (USD) to substitute for a friendship in equivalent happiness. Would you sell a treasured relationship for that sum? What would you buy with it? Half of a Porsche? A kitchen renovation?

Jean Baudrillard’s idea that rich collectors demonstrate how “everything that cannot be invested in human relationships is invested in objects” can now be extended to us all, to every consumer—from respectable middle class families to rioting London teenagers.

Lingerie designed by Jasper Conran on the floor of a looted department store during the 2011 London riots. Photograph by Simon Dawson/Bloomberg.

Lingerie designed by Jasper Conran on the floor of a looted department store during the 2011 London riots. Photograph by Simon Dawson/Bloomberg.

Governments can index happiness, economists can measure it, designers can design it, and the market can exploit it. But where is happiness on a dead planet?

One of happiness’ most common causes, the most profound and transformative human emotion, is of course love. This is the stuff design covets. Brands now don’t just want our loyalty, they want our love.

Our brain changes when we’re in love. The dose of dopamine that allows for the pleasurable associations experienced when we’re falling in love can rewire our brain. We can replace old habits with new tastes and preferences that influence how we feel about and act in the world. Does this sound like branding’s dream?

Long before graphic design attained the finely tuned sophistication of contemporary commercial image culture, John Berger wrote that publicity steals the self-love of an audience and offers it back for a price. If our positive emotional associations can be hijacked by brands, our affections can be transferred in a physical feat of brain chemistry. Ecstasies can be evoked as surges of dopamine lower our tolerance for pleasure and forge new affections for any commodity. And once the dopamine’s got us going, oxytocin lowers our guard and induces trust and attachment.

Or in the words of one advertising luminary with a peverted flair for neuroplasticity: “Lovemarks reach your heart as well as your mind, creating an intimate, emotional connection that you just can’t live without. Ever. [...] Lovemarks are a relationship, not a mere transaction. You don’t just buy Lovemarks, you embrace them passionately. That’s why you never want to let go. Put simply, Lovemarks inspire: Loyalty Beyond Reason.”

According to the Satchi & Satchi website, Lovemarks was named one of the 10 best “Ideas of the Decade” by Advertising Age magazine. It shared this honor with other noble ideas such as “brand journalism,” “marketer as media,” and what must be the advertising idea of any and all decades: “consumer control” (this phrase means the same thing however you interpret it).

Stefan Sagmeister undergoing an EEG test in a scene from The Happy Film

Stefan Sagmeister undergoing an EEG test in a scene from The Happy Film

Graphic designers are suddenly issuing much advice about happiness. Vince Frost has published a book called Design Your Life. Stefan Sagmeister's book is called Things I Have Learnt in my Life So Far, his TED talk 7 Rules for Making More Happiness and his documentary The Happy Film. James Victore’s weekly YouTube series, Burning Questions, “teaches creatives how to illuminate their individual gifts in order to achieve personal greatness.” Bruce Mau’s Incomplete Manifesto for Growth begins: “Allow events to change you. You have to be willing to grow…” Mau was thinking big for design, but it’s hard to swallow this barrage of belief in capitalism’s technological innovations towards a merely more finely tuned status quo. Tying the bombastic phrase “Massive Change,” for example, to such stunted aspirations, is a maneuver only possible under the happy spell of design. In such a state of excited contentment, all the market’s mechanisms of exploitation and inequality dissolve, and the politics of denial do their dirty work.

Guy Debord, who Mau cites in his book Life Style, wrote: “Young people everywhere have been allowed to choose between love and a garbage disposal unit. Everywhere they have chosen the garbage disposal unit.” To choose love, as easy as it sounds, would be massive change, but Mau offers us efficiency enhancements and technology instead. The project’s striving towards “the welfare of humanity” soon becomes “nothing but the vicissitudes of profitability,” as Baudrillard put it.

But as frustrated as our happiness is by design’s detours, there’s always plenty to be glad about. As Michel Foucault said, “Do not think that one has to be sad in order to be militant, even though the thing one is fighting is abominable.”

Or abominable and confusing. So many of the arguments for the promotion of our happiness and in defense of branding are interchangeable for indictments against it. “Brands are now writing the next chapters of our human journey. The transparency provided by technology does not remove the value of well-crafted stories, and never will. In fact, the more people interact, question and challenge brands’ narratives, the more engaged they will be. Beyond telling stories, brands are now allowing every one of us to be the story. Evolve in the dawning of a brand new world or become the prey.” These are the words of Sérgio Brodsky, an “internationally experienced brand marketing professional,” attempting to counter an article in the New Yorker titled “Twilight of the Brands.”

From Vance Packard's The Hidden Persuaders to Naomi Klein’s No Logo to Lucas Conley's recent Obsessive Branding Disorder there have been popular attempts to raise the alarm. There is a dawning realisation, that contrary to the Brandologists’ claims, research and innovation is being distracted by the substantial resources invested in branding, that promised improvements in products and services are deferred while their promotions get sleeker and slipperier, and we’re left empty handed, or with fistfuls of literal junk.

Pages from the Organisationsbuch der NSDAP, 1937

Pages from the Organisationsbuch der NSDAP, 1937

These foggy promises have a murky history. The late 19th century saw the rise of companies like Coca Cola and AEG with their advertising and design-led global aspirations. But branding is as much a totalitarian as a totalizing ideology, with its authoritarian intolerance of any values existing beyond its grasp and its way of “transcending all diversity,” as Carl Schmitt promoted Nazism. We need to heed George Orwell’s advice that “the word ‘Fascism’ is almost entirely meaningless ... almost any English person would accept ‘bully’ as a synonym for ‘Fascist.’” Still, it’s worth remembering that the bullying propaganda of branding could have begun with Hitler’s National Socialists. The Swastika and its omnipresent applications in 1930’s Germany saw the historical genesis of fully realized systematically programmed, contemporary branding methodology. The recent surge in interest about historical style guides somehow ignores the field’s foundational document: the Organisationsbuch der NSDAP (Organizational Handbook of the National Socialist Party), a branding blueprint covering every aspect of Nazi public communication.

As for graphic designers, we can part with much misery by breaking our ideological indenture, by rejecting branding’s totalitarian rhetoric. And we can side with happiness by responding to the real needs of the environment, communities, and individuals, rather than the priorities of privilege. Design can enable, rather than counterfeit and exploit human relationships. Designers can promote connection, not just consumption, so that the possibilities of happiness are not stylishly and systematically assaulted in the endless mire of mass representation.

Ultimately, what does anyone really know about finding happiness, except maybe that searching for it is futile? It is useless because the one thing we do know is that real happiness poises on a paradox contradicted by design’s devotion to consumer capitalism: happiness is intrinsic, not extrinsic, to us and yet we depend on each other in order to be human. Life is, as the Buddhist saying goes, ten thousand joys and ten thousand sorrows, and $60,000 or half of a Porsche won’t budge this balance one bit, no matter what the self-help entrepreneurs, brand gurus, and advertising mad men are selling. Our ideas and expectations of happiness can, and should, expand to include each other and all that sustains us.

Part 2: Conflict

Whose hearts must I break? What lies must I maintain?

– Through whose blood am I to wade?

Arthur Rimbaud

But what of the obstacles to visual communication becoming a vital language of this interdependence, to preventing the veiling of inequality and the hijacking of common aspiration?

Graphic design relates to conflict in at least two important ways. The first is by destructively concealing it. The second is by productively revealing it.

The concealing of conflict is, of course, the camouflaging of power. It’s the distracting seduction of consumer novelty. It’s the dirty engine of consumer culture, pumping out mental and atmospheric pollutants, hazy sceneries of shifting spectacle. Branding is now what we call these strategies of aestheticizing the concealment of social and political conflict. The global shock at Trump’s election victory is the veil tearing.

Although utterly superficial and cynical, branding is actually more significant than even its cheerleaders claim. Everyone now has opinions about branding, and everything — from your haircut to your handwriting — is spoken about in terms of branding. It’s as if the phenomenon isn’t simply a recent opportunistic dogma, but rather some kind of evolutionary objective. The ubiquity of the word is a candid index of neoliberal victories. Is there a corner of our culture still untainted by branding? Branding is a symptom of consumer capitalism’s failings, but not only a symptom. Branding has now breached the last barriers to advertising’s voracious environmental and psychological penetration. The heretofore stubborn evidence of coercive corporate power, of real social and political antagonisms, is hereafter elegantly “branded” away. This is design’s complicity in maintaining social inequity, disadvantage, and atomization. The designer is daily obscuring and reinforcing hierarchies of privilege and class division.

But these are just the obvious consequences of omnipresent branding. Less obvious is its colonization of social organizations, non-profits, public institutions, and geographical territories, so that even those entities with explicitly independent or oppositional agendas are displaced and transformed.

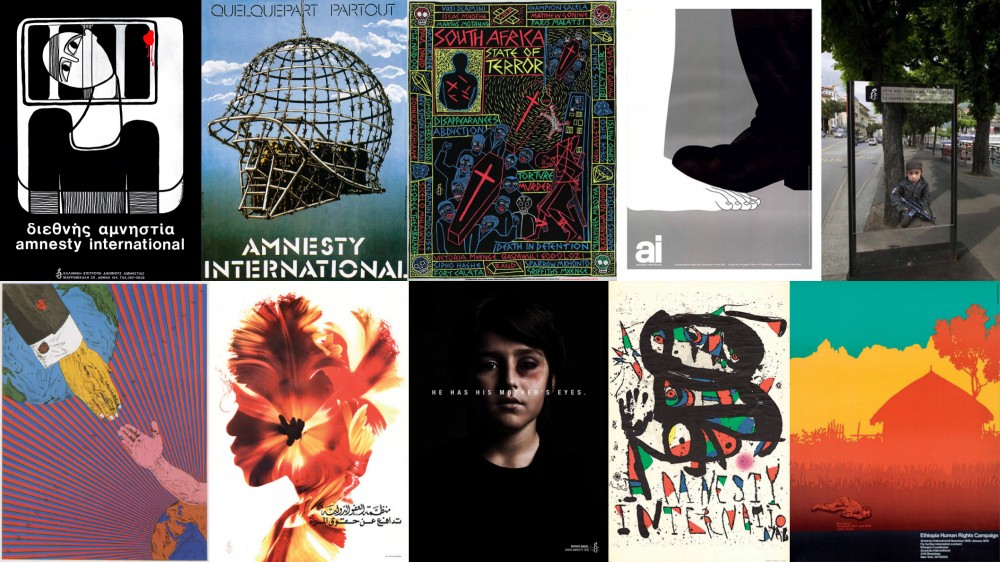

Here’s a fairly random selection of 20 Amnesty International posters. The first half were created prior to 2008, and the second half after 2008, when Wolff Olins implemented a global branding campaign.

Amnesty posters pre 2008 Wolff Olins’ global rebrand.

Amnesty posters pre 2008 Wolff Olins’ global rebrand.

Amnesty posters post 2008 Wolff Olins’ global rebrand.

Amnesty posters post 2008 Wolff Olins’ global rebrand.

Isn’t this is the difference between expressive human communication (for a human rights organization, after all) and corporate messaging? The difference between diverse, imaginative, visual provocations, and an emasculated voice, both formally and rhetorically? Is this not the waning from illustrative to photographic, from colorfully carefree to carefully approved, from compositionally fluid to rigid, symbolic to indexical, metaphoric to concrete, from unexpected to predictable? My point is not that all the pre-branding instances here are great and all the branded ones bad. The real problem is that this general devolution of communication isn’t likely to stop at the aesthetic.

It may not be possible to understand how this change affects an organization like Amnesty International — to sift the communicative and constitutional consequences. But insisting that the results are all positive is not honest. While I’m not claiming that there’s no room for consistency in visual identity design, isn’t the uncritical application of any communications methodology asking for trouble? To me, these posters illustrate that the recent semantic shift from terms like “design” and “visual identity” to “branding” was necessary to define an increasingly dehumanizing process. The historical application of the term “branding” from livestock, slave, prisoner, and product identification to the expression of personal values has a consistent trajectory.

Ask anyone who works in a public university, for example, how deep the bureaucratic agendas of corporate marketing have seeped into the fabric of their institution. This communication is not just “consumer facing;” it is internally absorbed and manifested at best as a demoralized academic culture, and at worst as a debased common good. The cynical advertisements become hallowed mission-statements. And increasingly, the reputational contrivance and competitiveness of branding in the public university sector does not merely reflect its gradually corporatized culture — it is also fueling the change. Here in Brisbane, higher learning institutions are all “Universities for the Real World” (so goes a prominent institution’s brand statement). Perhaps “Universities for the Perverse Whims of the Marketplace” just lacked a little poetry? For students, that’s the reality of “reducing the worth of a thing to the price of the thing, and the worth of a person to the wealth of the person… of defining your value exclusively in terms of your activity in the marketplace” as William Deresiewicz recently put it. And for staff, it’s the real world of pressurized and precarious contract employment, bureaucratic barriers, and impossible workloads.

The mindless conformity to branding principles is transposing fundamental priorities. Standards for appropriate corporate communication infiltrate public institutions, democratically elected governments, nation-states, geographical regions, non-profit organizations, and other social enterprises whose very missions are to resist homogenizing values. Branding is regulating critical agency and subtly directing ethos.

Of course, these brandings are already reflections, collective representations, and myths that have been inverted, overturning culture into nature so that, as Roland Barthes wrote, “what is nothing but a product of class division and its moral, cultural and aesthetic consequences is presented as […] Common Sense, the Norm, Right Reason and General Opinion […]”

These myths have long made it unfashionable and impolite to even mention class. Manufacturing has mostly migrated out of developed countries, but because we can't see it, do we somehow think it has vanished, and do we assume that class struggle has vanished also? And did we expect the inequality — experienced so acutely by those left behind, and so lethally exploited by Trump in the US heartland — to just fade away?

Branding’s veiling of social antagonisms can be demonstrated as literal as well as figurative. For example São Paulo became famous as the first city in the world to ban what the industry calls ‘out of home’ advertising – the commercial billboards and signage that blanket most cities. When the hoardings were removed, the stark poverty of the crumbling favelas was much harder to ignore. The act of ‘debranding’ São Paulo helped unmask the divide between the promoted aspirations of consumer luxury and the reality of rampant disadvantage. It visually confessed class conflict.

The Paraisópolis favela next to the gated Morumbi complexes. Image by Tuca Vieira.

The Paraisópolis favela next to the gated Morumbi complexes. Image by Tuca Vieira.

So if design is complicit in these processes, how can it be redeemed? With all our skills and creativity, we can highlight what is airbrushed away in the name of marketing. We can render alternatives. We can do much to change the meaning of things, and therefore change the world and our role in it. This is what design theorist Tony Fry calls “recoding,” an assumption that a total transformation of the material world towards sustainability is not possible, but that recreating meaning is. Or like Kurt Wagner from Lambchop sings in his synth-pop side project HeCTA: “You shouldn’t have to change a thing except your mind”. Even if designers’ critical responses are sometimes tiny gestures against a greater force of commercial manipulation, isn't doing nothing active acquiescence?

Design is unavoidably an art of conflict. It inevitably attempts to organize conflicting social relations in time and space, just as Daniel Bensaid described politics as “an art of shifting the lines (of changing the balance of forces) and of breaking apart the march of time.” We are entering a crisis of civilization where, as Bensaid wrote, “the essential thing is to give the non-fatal side of history its proper opportunity.” This opportunity will require us to design democratic spaces for productive resistance, and for these realms to repel the ideological weapons of the market, among them the petty, lethal enchantments of branding.

+

Jason Grant 2016

Based on talks given at the Asia Pacific Design Library’s lecture series.