Brion Gysin

Brion Gysin:

Tuning in to the Multimedia Age

Brion Gysin: Tuning in to the Multimedia Age,

Edited by José Férez Kuri

Review published in Eye 50

Long overshadowed by the art and artists he inspired, Brion Gysin was a prototype twentieth century multimedia pioneer. With an insatiable intertextual vocabulary he warped from poet to painter, inventor to performer, creating a small but profoundly influential body of work. Brion Gysin: Tuning in to the Multimedia Age comprehensively gathers these images and ideas together for the first time.

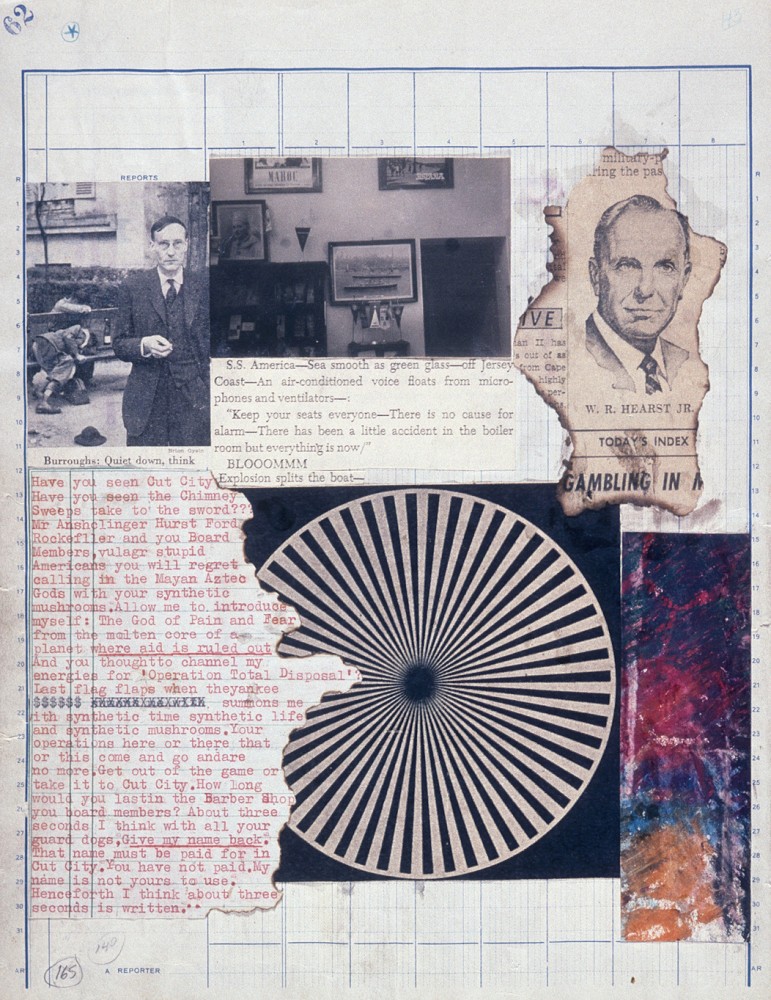

Untitled (W.R. Hearst Jr.), collage for The Third Mind C 1965, by William Burroughs & Brion Gysin

Untitled (W.R. Hearst Jr.), collage for The Third Mind C 1965, by William Burroughs & Brion Gysin

The collected essays by critics, friends and contemporaries suggest the artist’s work was less important than the energy of his ideas and personality. Gysin’s direct influence on the writing of the Beats, popular music and painting has helped shape a broad range of contemporary avant-garde activity. In graphic design for example, Jonathan Barnbrook’s syntactically mutating typeface Burroughs (“which creates nonsensical poetry from any word specified in it”), could have been titled Gysin. When digital technology was still learning to crawl, and just months after he shared his discovery of ‘cut-ups’ with William S. Burroughs, Gysin was already producing computer generated ‘permutation poems’.

Gysin and Burroughs were lifelong friends and collaborators, and the editor acknowledges Burroughs’ encouragement in promoting the artist’s memory as the genesis of the book. Burroughs contributes an essay that begins to reveal Gysins’ spiritual and formal legacy in his own work but veers into elusive interpretive prose – exposing the hazards, even for the West’s greatest post-war experimental writer, of attempting to penetrate images with words. Burroughs had no doubt about his friend's impact: “Each time I look at this picture I see something I never saw before in the whole world.”

Honest and privileged essays follow from friends such as Gregory Corso, John Giorno and Felicity Mason. These texts still reverberate from the impact of Gysin’s death and read partly as intimate eulogies. This familiar tone is well balanced by focused critical essays from Guy Brett, Barry Miles, Nicholas Zurbrugg, and Bruce Granville. John Gieger concludes with a revealing biographical text.

Gysin was many different artists, rarely empirical or dogmatic – an American born in England of a Canadian mother and Swiss father and living most of his life in France and Morocco – he was indifferent to hegemony, and the false polarities of divided cultures and divorced mediums.

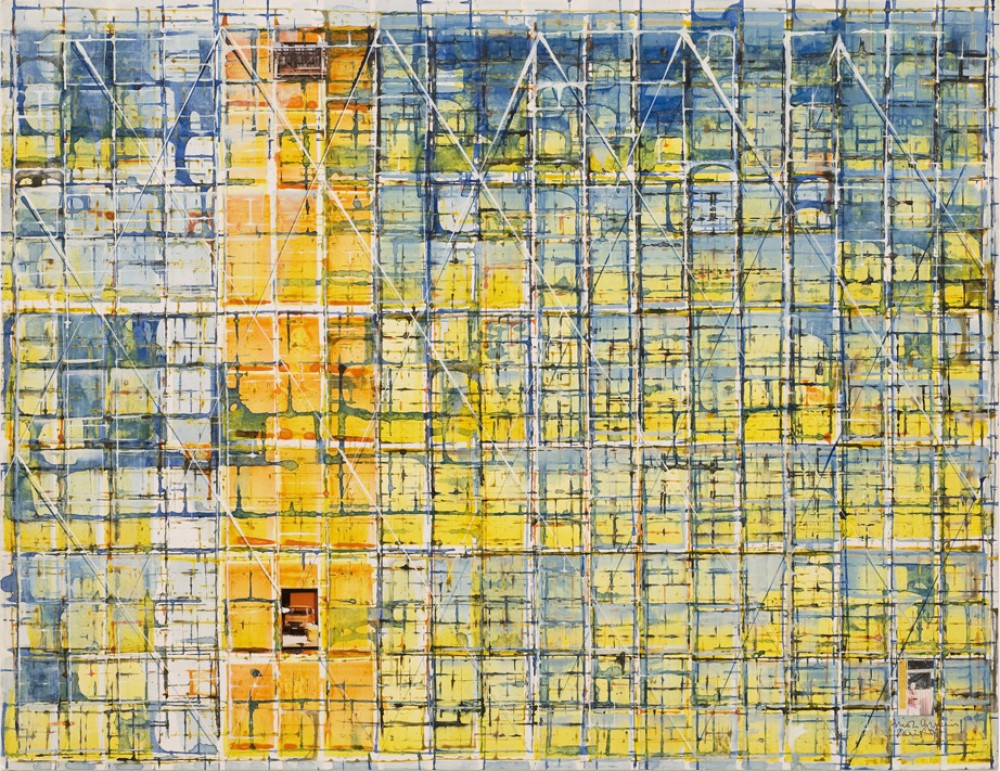

His early surrealist paintings moved on to Saharan desert landscapes and then to unprecedented calligraphic paintings that drew from automism, Japanese and Arabic calligraphy, gestural abstraction and cabalistic magic. The layering of horizontal Arabic script that “rushes across the picture space from left to right like and army with banners” and vertical Japanese calligraphy that “dangles like vines” produced a graphic web that established the structure and strategy of methodical spontaneity Gysin would apply to his subsequent painting, writing, sound poetry, permutated poems, photo based work and performance.

The calligraphy grids eventually suggested a roller apparatus capable of painting infinite mosaic patterns; a formal device that Gysin would later interrupt with gestural marks and biographical photographs exploring the integration of linguistic signs and dynamic surges of optical energy. He ultimately identified the grids with the modernist facades of the contemporary urban environment – metaphors for the “society of control”.

Untitled 1977, Gouache, ink, and photo-collage on paper by Brion Gysin

Untitled 1977, Gouache, ink, and photo-collage on paper by Brion Gysin

The Multimedia Age of the book’s title is of course the Postmodern Era, and many contributors attempt to position Gysin as ideologically unbound – merely exploring “multiple agendas across multiple media in a spirit of unrestrained curiosity,” as Nicholas Zurbrugg writes. However Burroughs and Gysin understood the cut-up technique as a means to subvert the impulsive systems of power inherent in language – a revolutionary weapon against the “agents of oppression”. While mounting a drawing in late 1959, Gysin accidentally sliced through a stack of newspapers. Rearranging the segments, he discovered a collage of words that composed revelatory new texts and offered the possibility of updating a lagging art: “writing is fifty years behind painting.” (Coincidently, like Tristan Tzara, who pre-empted cut-ups by pulling words from a hat to compose poems, the teenage Gysin was allegedly expelled from the Surrealist movement for non-conformity by Andre Breton.)

The transgressive, magic force of art was not entirely a construct of Gysin’s drug soaked residency at Paris’s Beat Hotel. Gieger relates how at the beginning of 1986 Keith Haring and his friend George Condo visited Gysin languishing in hospital. Shocked at his apparent proximity to death they resolved to paint to save the artist’s life. They worked all night to complete the painting, and Gysin walked from the hospital the next day, postponing his inevitable death to cancer on July 1986.

+

Jason Grant 2004