Coming Home

Coming Home

extract from a presentation to the AGIdeas International Design Week, Melbourne 2005

Returning to Australia after living for a few years in the UK,

I was walking through Brisbane’s city centre and noticed these banners everywhere:

‘Downtown Brisbane - it’s happening!’... while I was away, Brisbane had happened! I tried to imagine similar banners hanging in Paris or London or Tokyo – Tokyo de Nanika - ga okoru! Promoting a city like it’s a department store might have some kind of marketing logic, but what are these signs actually advertising – a vibrant and diverse modern capital, or cultural insecurity and bureaucratic pretension? ‘It’s happening’ – if we really need to be told, it’s a safe bet it’s not happening at all – or if it is happening, it’s not happening the way we want it to. On its own terms it’s still ridiculous. Even the dimmest marketeer understands to claim cool is to kill cool. The banners don’t celebrate a city at all – they bury it.

We hope there are other voices that have the potential for creative community expression, avoiding a top-down declaration of forced status and relevance.

...

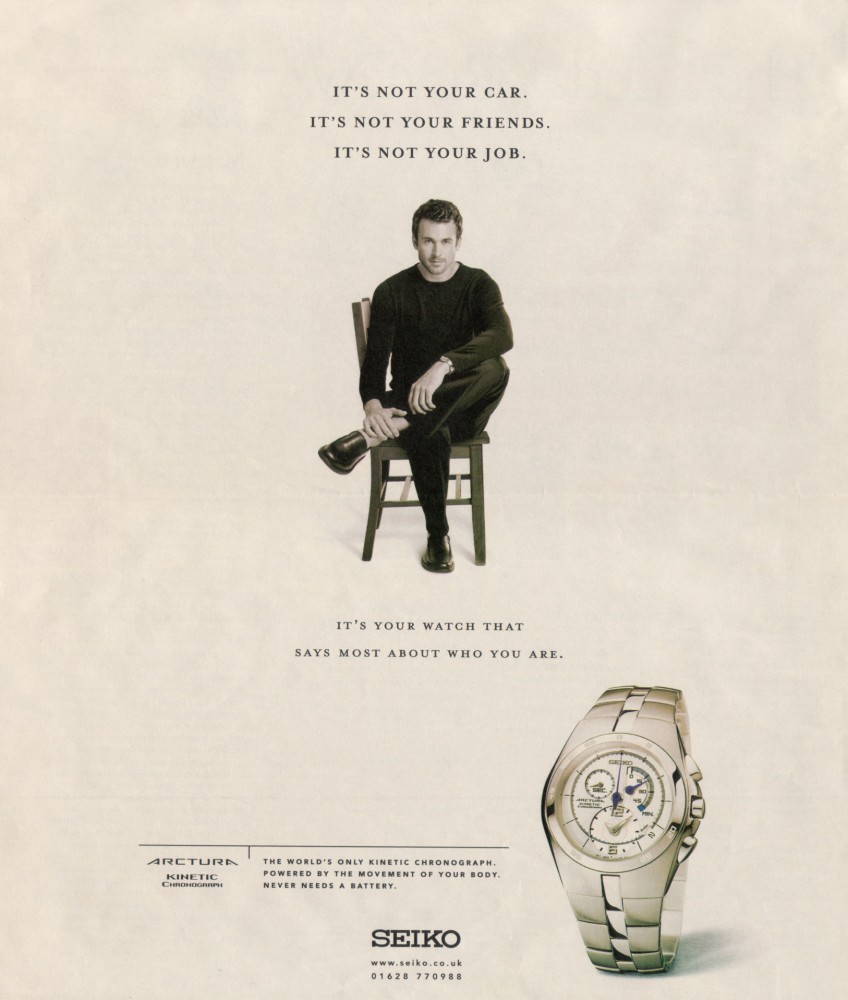

I found this in a magazine recently:

I know it’s easy to make fun of crass and obviously manipulative advertisements (and usually more satisfying than actually buying the product). Many ads appear to ignore the critical sophistication of their audience. Then again, some appear to encourage and exploit this cynicism as a strategy for neutralising deeper criticism – a kind of ‘contract of cool’ between advertiser and consumer that double bluffs stupidity. But we all know that advertising is forever like the virus developing resilience to medicine, and now there’s this new tactic that is somehow a combination of both of these approaches.

This ad represents a recent strain of advertising embodying a kind of post-ironic transparency that assumes an unconditional surrender to the avaricious culture of hyper capitalism. Back in 1956 Vance Packard’s book The Hidden Persuaders presented a spooky vision of “American super-advertising-scientists” casting subliminal consumer spells on a defenceless public. Nearly fifty years later ads are expressing their persuasive content and ideological constitution so openly, that any notion of subconscious manipulation seems irrelevant.

It’s not your car. It’s not your friends. It’s not your job. It’s your watch that says most about who you are.

Advertising often distorts our image, but it can also reflect us with deadly accuracy. I reckon this ad for Seiko watches takes our measure without flinching, and our values, concerns and priorities are pretty plainly exposed. No beating around the bush, no subtle implications or hidden meanings – ‘what you buy says most about what you are’. Although this statement wouldn’t fit as well with products such as, say, diesel fuel or adhesive rat traps, it isn’t an argument anymore, it’s a fact, and we are the proof.

Our contemporary culture, the culture of buying and selling stuff, is so supremely confident that these lies are now truths. Cocky consumer capitalism may have triumphed, but although its propaganda continues, as John Berger writes, to steal our self-love and offer it back to us for a price, we are still human. If these ads are a gauge of the success of an ideology, then our resistance to it will be the measure of our humanity. Our political, ethical and spiritual choices, not our watches, our sneakers or our mobile phones, will say the most about who we are.

Part of the reason designers really matter – for the better or worse – is that our craft is one of the most common vehicles for the dominant ideology. Berger wrote that publicity turns consumption into a substitute for democracy. I believe we saw this demonstrated at the last Federal election here in Australia – this link between consumption, material aspiration and political cynicism. A leader that has contempt for social justice and democracy, that has been caught lying to us about the war in Iraq and about children overboard, who is responsible for re-routing, imprisoning and torturing innocent asylum seekers, and who has generally undressed the worst parts of our nature in order to cling to power, was re-elected this time round for fear of a threat to our consumer novelty and material comfort.

There’s just no such thing as an apolitical stance. For example, social power is reflected and embedded in the images we consume. Representations of gender, race, class and sexuality are dealt with daily by designers. We make subtle choices about who to include in an image and how to represent them.

But any progress towards redressing the balance of, let alone overcoming a dominant discriminatory value system can be instantly neutralised by name-calling (‘PC’, anyone?), and eventually, by a pre-emptive self-censorship. The Australians here have all witnessed the Howard government’s wielding of the term ‘black armband history.’ As soon as Terra Nullius was legally recognised as a fiction, and the heroic myths of our colonial history were threatened, the Government urged us to remember the good times. Don’t look at the massacres, exploitation and injustice as a defining characteristic of Australia’s recent history, but rather Aussie ‘mateship’ and sporting victories.

This struggle for history is perpetual, and is written, as they say, by its victors. In Stalin’s Russia, perceived political enemies were erased from photographs and documents – this act of visual deceit merely mirroring their actual ‘disappearance.’

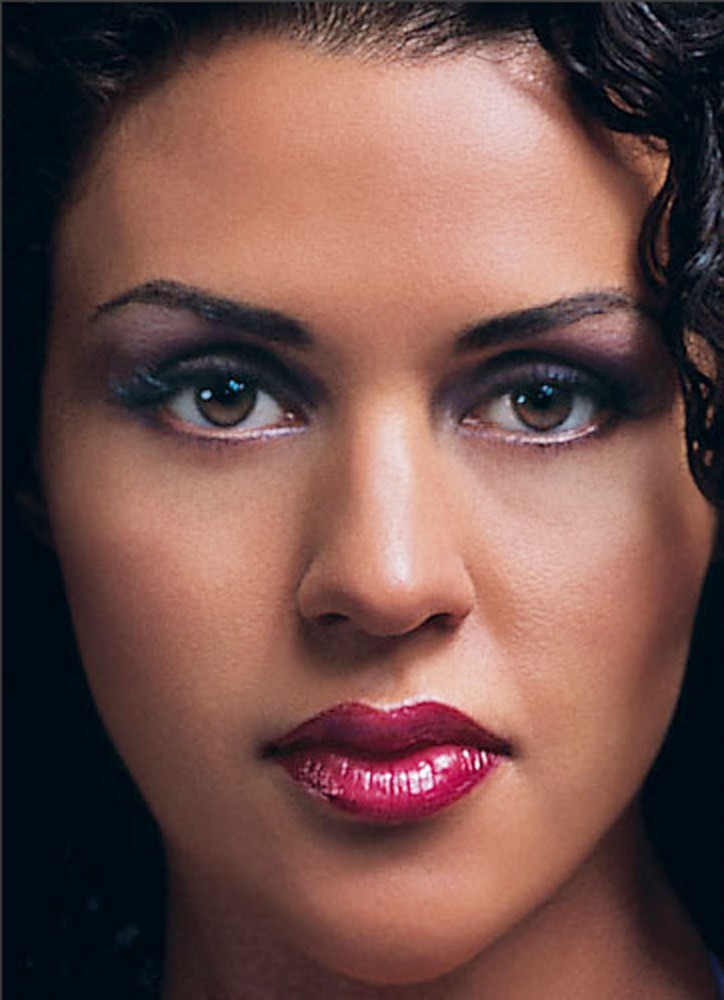

Retouching by Greg Apadoca

Retouching by Greg Apadoca

Of course now we have digital image editing, rendering impossible ideals of beauty, but the really sinister manipulations are still the stubborn exclusions from our image landscape... a black face, a gay kiss, a wheelchair, a size 16 dress...

These eerie absences eventually define our aspirations. Our culture promotes and rewards values that protect established power structures and actively ignores or suppresses alternatives. A poverty of alternative images is not exactly the cruel exclusion of class privilege, but it is not unrelated either.

It is no coincidence that the most alienated members of our community are also the least represented in our popular imagery. Although a more diverse representation of the rich complexity of our culture would be welcome, the real struggle is for a society that actually values this diversity. This is where we come in, because the more image-saturated our lives become, however, the more likely it is that one won’t occur without the other.

While any common project, or movement, of graphic resistance is tentative and unproven, if we take it for granted that design animates desire to accumulate, distract and dominate, then why can’t we can also imagine design’s potential to liberate. Design doesn’t just express our culture – it is us. It works – if it didn’t, clients wouldn’t pay for it. We just need to aim it in the right direction.

+

Jason Grant 2005